quinn lawyers

Surrogate innocents in legal limbo

Kyla Booth and her husband Matthew tried for 10 years to have a baby before being told Booth would never carry a child to full term. Adenomyosis and blocked tubes were just some of the fertility hurdles she faced. Instead, the Adelaide teachers travelled to Thailand and with the help of a surrogate mother now have two precious girls — Sabai, 4, and Isara, 2.

But a full Family Court decision this month has left the sisters — and thousands of other Australian children born via overseas surrogacy arrangements — without legal parents. The decision has prompted calls for urgent legislative change so children are not left in a legal limbo, and potentially stateless.

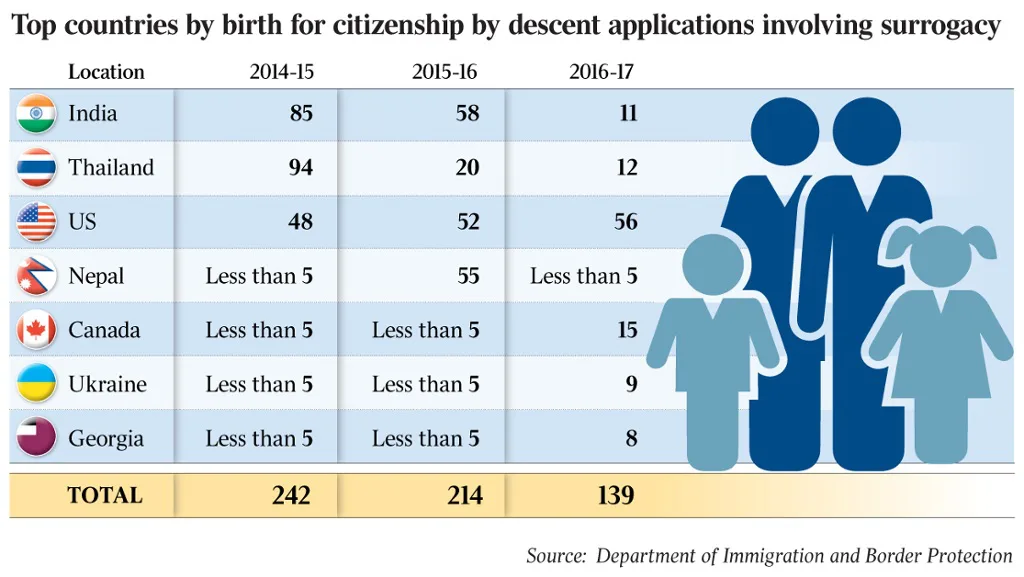

International surrogacy is a booming business and Australians are among the world’s most enthusiastic clients.

As destinations such as India, Thailand and Nepal have shut their doors to foreigners seeking babies via surrogacy, Australians have shifted their business to the US and Canada, and countries with less certain safeguards for surrogate mothers, such as Georgia, Ukraine and even Kenya.

About 600 babies born via international surrogacy arrangements were handed Australian passports during the past three years, according to Department of Immigration and Border Protection figures.

This total does not include Australian permanent residents and others granted visas to bring babies into the country.

Now the parentage of all of those children, and others born in previous years, has been put in doubt.

Family Court Chief Justice Diana Bryant — one of the judges involved in the recent full-court decision — is among those agitating for legislative change.

She tells The Australian the situation is not “satisfactory at all”.

“The states and the commonwealth need to get together and sort out who has responsibility and deal with it,” she says.

At the moment, the commonwealth Family Law Act leaves it to state and territory legislation to determine the status of children born through surrogacy. However, no Australian state or territory recognises children born via overseas arrangements, meaning they fall through the legal cracks.

In its decision published last week, the Family Court refused to recognise the parentage of a Melbourne couple known as “Mr and Mrs Bernieres”, who entered a commercial arrangement with a surrogate mother in India.

Their girl, now 3, was created using Mr Bernieres’s sperm and an egg from an anonymous donor, with the foetus carried by the surrogate mother.

The three judges said it was not open to the court to fill the “legislative vacuum” that existed for children born via overseas surrogacy arrangements — this needed to be fixed by legislation. “The unfortunate result of that conclusion is that the parentage of the child here is in doubt,” they decided.

“There is no question that the father is the child’s biological father, but that does not translate into him being a parent for the purposes of the act,” the judgment says. “Further, the mother is not even the biological mother, and thus is even less likely to be the ‘legal parent’.”

The decision has caused deep concern among lawyers and families and prompted demands for immeditate change.

Previously, individual judges were prepared to recognise couples such as Mr and Mrs Bernieres as legal parents. But this is the first time the full Family Court has ruled on the issue.

Family lawyer Stephen Page, who is an expert in surrogacy law, says the outcome for children is “just nuts”. “If you follow the logic … the Family Court judges said in effect the Australian couple are not the parents,” he says.

“The obvious inference is either the child has no parents, which is a dreadful outcome and cannot be right, or the people who are the parents are the Indian couple — the surrogate and her husband.

“But when you look at what they did, they aren’t parents under Indian law, they said they were never going to be the parents, they have never cared for the child and don’t have any genetic relationship with the child.

“You look at this and you go: What a strange outcome.”

Page worries the decision could leave children stateless because some countries, including India, refuse to recognise surrogate mothers as legal parents.

Until now, the Immigration Department has looked at social, legal and biological factors to decide if a child is eligible for Australian citizenship by descent. But if it decides to follow the Family Court decision, then children born through surrogacy may no longer be recognised as the child of a parent for citizenship purposes.

Page says this would be a “dreadful outcome”.

Family lawyer Paul Boers, who acted for the Bernieres, says there are other potential complications. If the couple die intestate, their little girl wouldn’t necessarily be entitled to an inheritance, and if they separated, the surrogate mother and her partner would have to be joined in any family law proceedings, causing unnecessary complexity and expense.

It’s not as if the problem has come out of nowhere.

Back in 2013, the federal government was warned in a report by the Family Law Council that “a large number of young children” born via commercial surrogacy arrangements appeared to be “growing up in Australia without any secure legal relationship to the parents who are raising them”.

It recommended a relatively easy legislative fix — a new federal law that would allow for parentage to be transferred from surrogate mothers to intended parents, provided specific safeguards were met — including that the parents had acted in “good faith” and there was evidence of the surrogate mother’s consent.

However, this would be inconsistent with laws in NSW, Queensland and the ACT, which make it an offence to engage in overseas commercial surrogacy, and contrary to the spirit of laws in all states and territories, which allow only altruistic surrogacy, opening up a fresh can of legal worms.

Read More: The Australian

Back to News